By Laura Howard

UNH Nursing Program

It was Wednesday, and I took my usual seat three rows from the front of the classroom. Prepared to listen to that day’s classical piece, I reached for my Music History notebook. My professor dimmed the lights as a romantic scene from the film Ocean’s Eleven played on the screen. Debussy’s Claire de Lune could be heard in the background.

The scene ended, and my professor asked us to watch the scene again. This time, I immediately sensed something missing. I heard the two main characters speaking. I heard traffic and passersby shouting in the background. But a key element had vanished from the soundtrack – there was no music. The scene lost both its former beauty and the emotional connection made possible by Debussy’s accompaniment.

Stop right now, wherever you are, and take a moment to listen.

We are constantly exposed to a range of sounds – laughter, car horns, driving rain, birdsong. And while we seldom pause to hear these sounds, we always notice when the world goes eerily quiet. The music of nature is quickly being transformed, drowned out, and silenced by expanding human populations.

In her classic book Silent Spring (1962), Rachel Carson challenges readers to explore what life would be like in the absence of sound, and what a quiet world might mean. “On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound …”. Scientists have begun to study the sounds of nature to better understand species and to gauge the health of the environment.

Sounds in the natural world can be categorized according to their origins: biophony (sounds from biological organisms), geophony (sounds from non-living things, such as wind and water), and anthrophony (human-made sounds). Together, these sounds make up what ecologists call the soundscape. The study of soundscapes can be a tool for detecting human-posed threats to wildlife.

Bioacoustics research provides insight into animal behavior and evolution, which can aid conservation efforts to protect species at risk of extinction. For instance, the threatened African Elephant has been widely studied for its advanced language skills. A recent study (published in 2014) discovered that African elephants have adapted their language to include a specific warning rumble, comparable to a vowel-change in human language, that is used only to alert others that African tribesmen are present. While this is fascinating, and offers a window into their intelligence, it is distressing that the intensity of poaching has caused the elephants to evolve their language to warn one another about us humans.

Whales are similarly known for their complex communication system, and scientists have been recording and studying whale songs since the 1960s. Javahar Mariwala tells the story of the scientist Roger Payne who wondered whether the beauty of whale song could be used to stop the whaling industry. Payne teamed up with singer-songwriter Judy Collins to bring whale song to the people. Collins incorporated Payne’s whale song recordings in “Farewell to Tarwathie,” which became popular worldwide and helped to establish an emotional connection between humans and whales.

Perhaps if we listened more, if we took the time to hear what other species are saying, we might feel our connection to nature. And we might do less harm.

Recently, I challenged myself to observe the biophony and geophony surrounding me. Over the span of a few days, I consciously listened. Initially, it was difficult to hear past the anthrophony, but I listened hard and I began to refamiliarize myself with the sounds of nature. The sounds of spring rain hitting the pavement. The sounds of wind blowing around the leaves left over from last fall. The sounds of birds chirping from the bushes and trees. I listened, and soon I found myself seeking out opportunities to set aside my schoolwork for a moment, slow down, and listen for the music of nature.

If you feel inspired to, I invite you to consciously listen. Listen to all the different layers of your soundscape. And imagine what it would be like if one of those layers went missing.

Laura Howard is a Nursing major at the University of New Hampshire. Laura grew up at the base of Mount Monadnock in New Hampshire, and has always appreciated the outdoors. She spends much of her time exploring nature — biking and hiking in the warmer months, and skiing and snowshoeing throughout the winter. Laura is also a musician, and through her growing love of music she has found great peace and beauty in the sounds of nature.

Editor: JLP

‘Hearing’ (cover photo): seriykotik1970 (CC-NC)

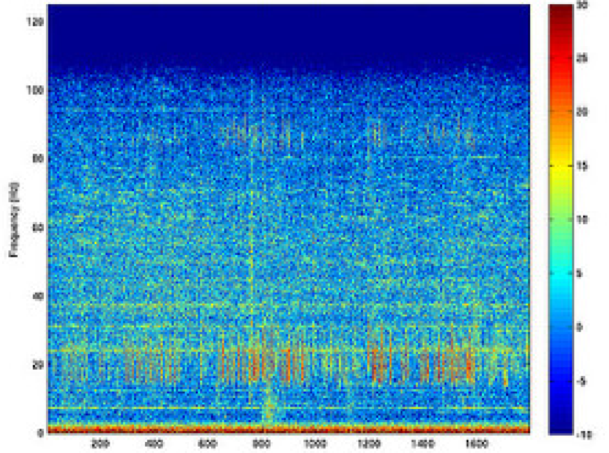

Spectrogram, whale calls: The Official CTBTO Photostream (CC-BY)

References

Blanc, J. (2008). Loxodonta africana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T12392A3339343.en.

Grenoble, Ryan. (2014). Researchers: Elephants Have Developed a Human-Specific Alarm Call. Huffington Post. Retrieved from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/08/elephant-human-alarm-call_n_4921731.html

Harris, Richard. (2011). Scientists Tune in to the Voices ‘Voices of the Landscape’. NPR. Retrieved from

http://www.npr.org/2011/03/26/134425597/scientists-tune-in-to-the-voices-of-the-landscape

Joseph Slotis, Lucy E. King, Ian Douglas-Hamilton, Fritz Vollrath, Anne Savage. (2014). African Elephant Alarm Calls Distinguish between Threats from Humans and Bees. PLOS One. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089403

Mariwala, Javahar. (2015). Bioacoustics: Communication and Conservation. Soundscapes. Retrieved from https://sites.duke.edu/soundscapes/2015/11/24/bioacoustics-communication-and-conservation/